A few years ago, we sent a 50-year-old Ferrari 365 to auction for a client. Prior to sending the car we looked at the serial numbers and noted the chassis number stamped on the block in the expected place. Experience tells us what Ferrari serial numbers of this vintage should look like, and these looked original and ok. We told the auction the car appeared to have a matched engine and body. Looking at the tags there was no reason to suspect anything was amiss.

We had a surprise at the auction. There was quite a bit of interest in the car and several bidders took photos of the car’s tags and sent them to experts for review. One expert found a potential problem. He had a large database of Ferrari serial numbers, and he saw what appeared to be a conflict.

In the 60s and early 70s Ferrari stamped V12 chassis numbers on the frame head, the body tag, and the engine block where it meets the transmission. The engine also has an internal engine number, separate from the body number, stamped above the chassis number mark. The internal engine number should be unique. In this case, there was a record of another car having the same internal engine number.

This photo shows the numbers on our clients car:

This is a photo of another car's engine, seemingly with the same (upper) block casting number:

These two cars have chassis numbers almost 200 cars apart, but the top number appears the same, putting the authenticity of our client’s car in question. The auction pulled it from the sale. That started a 14-month effort to answer the question: Were the numbers on our client’s car original and authentic, or not?

We tried to track the car’s owners, but only had limited success. The Ferrari records showed our clients car was delivered new to a dealer in Toronto, and we followed the trail back 25 years from the present owner, but the period in the middle remained unknown. We could not determine anything about what was done to the car in those years. An engine swap was possible. Ferrari does not furnish casting numbers, or other numbers, outside their Classiche certification program.

We returned to the photographic evidence. I used Adobe Lightroom to enhance contrast and detail on the images, zoomed in, and looked very closely. Using the Adobe developing tools, I adjusted the images to show maximum contrast, and I set the colors as close to identical as possible. I did not retouch, add, or delete anything from either image.

This is the block number from the other car

Here is the block number on our client's car

There is no doubt these four examples are done in a similar style. Based on the evidence of these photos I don’t think we could say any of these was altered, but there may be multiple stamp attempts on the A1938 on one car. That said, the many similarities made me think all the stamping happened in the factory.

Here are the noteworthy points on the chassis numbers part of the stamping:

- The height of the chassis number boss on each engine looks roughly the same

- There is a light bevel across the bottom of the boss, same on both

- The grind marks run in the same direction, and the same grain spacing on both

- There is a line lightly scribed below the stamped numbers on both

- The surface finish of both is identical with respect to grain and grain direction

- The type face of the number stamps is identical

Several points of similarity argue that these two engines were stamped with the same stamp set:

- The 3 may be imprinted by the very same stamp, which is light across top

- The T has the same slight curl on both engines, at the top left

- The 9 is light in the top right on both blocks

- The stamp style is exactly the same, and different from other stampings on the cars.

All the above points make a strong case for the originality of the stampings. We looked closer at the "duplicate" A1938 number:

- On both engines enlargement shows the marks to be original. The surface into which 1938 is stamped is slightly curved, and the stamping is uneven on both engines. The stamping of the A is identical on both, and may have been done by the very same stamp (note matched thickness of bar in the A).

- The texture of the block shows that the 1938 numbers are original, though a digit may be over stamped on one. Re-stamping would destroy the original sand cast texture.

- Both 13989 and 13795 engines show a circular indent around the 1, probably from the body of the stamp.

- Both engines show evidence of multiple hits of the stamp hammer

- On the 13795 car the Blok number may have the last digit re-stamped 8 over 0 or 9, or vice versa. See angle in lower right. On 13989 the 8 at the end is very clear.

- On the 13989 engine the 3 is crooked and there’s an indent to its left, on 13795 that digit is clear.

Supposedly, Ferrari only used even numbers for these block castings so the observation that an 8 is stamped over a 9 seems unlikely but a 0 is possible and it's also possible the factory worker just made a mistake.

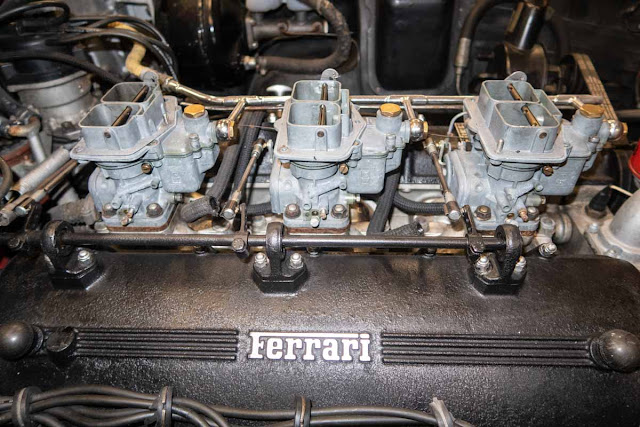

This is a frustratingly slow process that can take years to complete. Classiche inspectors look at every number and mark on the car. For example, we pulled the air filters and photographed the model and serial numbers of each carb to establish whether they were the correct ones, and the very ones they left the factory with.

All chassis marks were photographed and checked

The three-digit body stamps spoke to the authenticity of doors, hood, trunk, and even seats. Other numbers allowed the factory to check the differential and transmission.

In the end, Ferrari said the numbers stamped on our client's car were correct and original. They never commented on the other car, nor did they comment on the imperfections of the hand stamping that open the door. for challenges like this, decades down the road.

We like to imagine Ferrari and other carmakers have rooms full of files, with every details of the cars we love memorialized. If only that were true! Corvette lovers all know about the factory that burned down and took most of their records. Owners of prewar European cars lament the loss of those factories to bombing and wartime depredations. Many records from the 1960s are simply lost, and of course hand labor is by definition imperfect. A few factories claim to have records of every car built but I wonder how true that is.

A machine that is designed to stamp sequential numbers into a line of engine blocks will do its job consistently and reliably, as evidenced by the quality of numbering on new production cars. Old Ferraris and their ilk are not like that. They build engines one at a time, over days or months. There is no production line spitting them out stamped and finished every minute. Engine builders are imperfect; stamps are off center or hard to read. Errors get re-stamped. Workers are dyslexic or perhaps hung over, stamping 98 instead of 89 or 6 in place of 9.

Today, all we can give is our best judgement, and sometimes, as in this case, a lot rides on it.

One day the 13795 car may come up for sale, and this issue will surface again. Now that we have been down this road, and Ferrari stands behind the 13989 car's markings, where does that leave the other car? Perhaps the last digit will be deemed a 0, or perhaps Ferrari will say this is a duplicate, and a factor error. Time will tell.

Collectors often suspect fraud in these cases, but I find mistakes and omissions more common. Yet there are some fishy cars. There are certainly cases where Ferrari made 5 of a certain car, yet 7 examples appear to exist today. And there are restorations whose numbers look perfect, but later turn out to be the same as numbers on an original car in some barn.

In the creation of this article and the examination of these cars I want to thank Marcel Massini, who is probably the world's foremost expert on Ferrari numbers, codes, and details. Marcel is an unparalleled fount of knowledge on these cars. Here we are looking at Ferrari at Amelia Island on March 3, 2020, just before the COVID pandemic hit.

Until next time

John Elder Robison

No comments:

Post a Comment